Compression vs. Limiting

Here’s an interesting topic that came to mind the other day. It was prompted by the “tech notes” document associated with the free HD download from Kent Poon of Design w Sound, an audiophile producer/engineer based in Hong Kong. As I mentioned in a previous post, I downloaded his “Audiophile Jazz Prologue Part 4” recently. I also read the PDF file that states the following:

“DSD is a 1bit format, which cannot be mixed, level changed or processed. We use Switzerland Weiss SARACON software to convert multi-tracks DSD back to multi-tracks PCM 24bit/192kHz for post productions. It is worth to mention Weiss SARACON has a bandwidth around 40kHz. 24bit/192kHz convolution reverberation technology is applied, sampling from US Westlake Studios D Live Room and EMT140. The final 24bit/192kHz AIFF file has about 2dB limiting in order to bring up the overall loudness slightly, but still with extremely high dynamic range, listener is expected to crack up the volume 4-8dB than normal audiophile records. The final DSD 5.6MHz DIFF file is created by Weiss SARACON software too.”

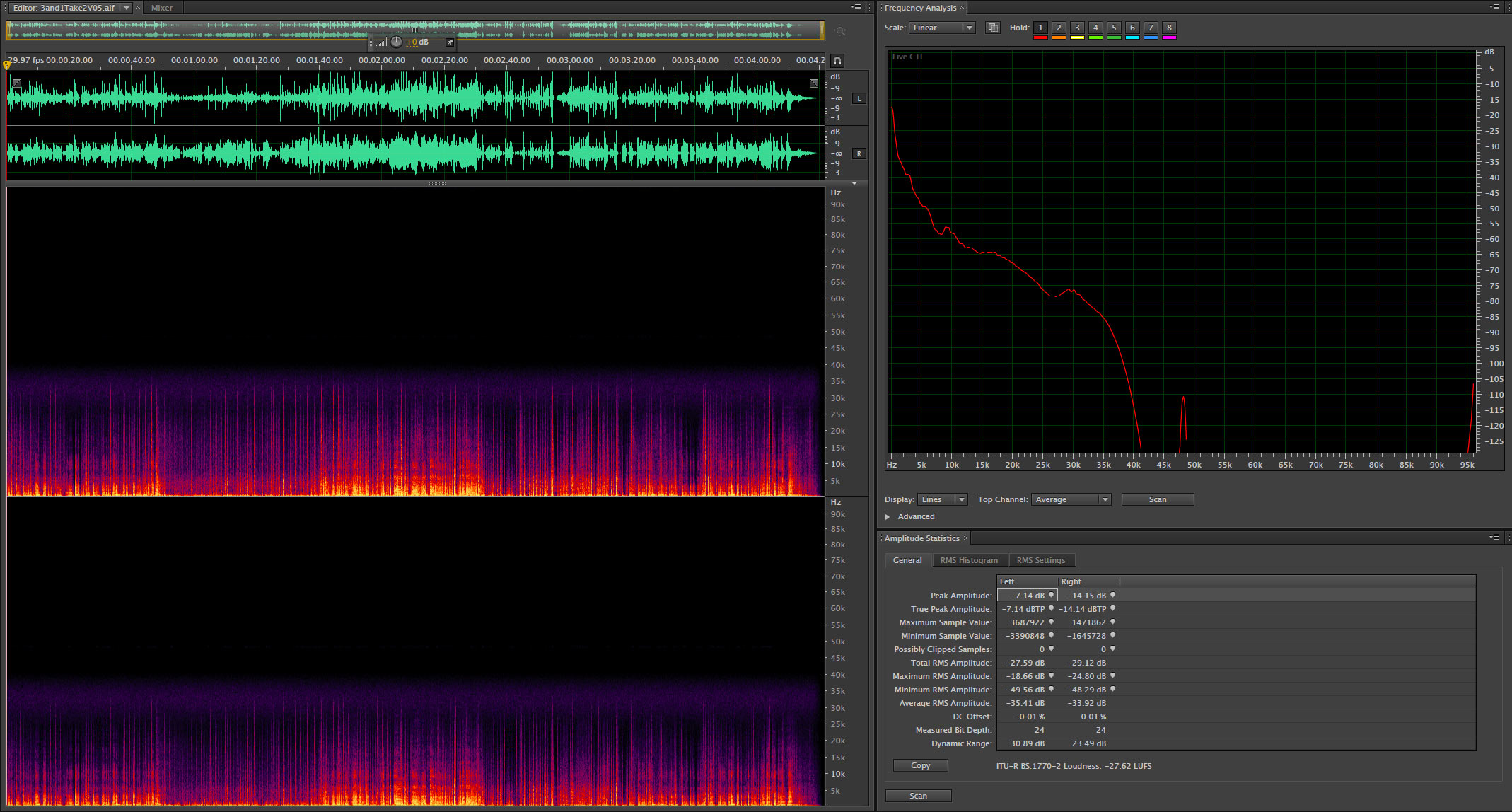

The recording was made using a Genex 9048 DSD recorder at 2.8224 kHz and 1-bit. But as we’ve seen is very common with engineers and producers that capture using DSD, the source is transferred to HD-PCM standards (192 kHz/24-bits in this case) for the post production steps. I ran the files through Audition and produced the following spectragraph of the sample file (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – The Spectragraph of Design w Sound Free HD-Audio track AJP4 at 192 kHz/24-bits (click to enlarge)

You can take away from this recording what you will. What I see is an original DSD 64 recording that has been transcoded to 192 kHz/24-bit PCM using SARACON software. The choice to use 192 kHz seems somewhat superfluous since the audio doesn’t extend any higher than about 35-40 kHz. This is undoubtedly the result of a Low Pass Filter being applied during the transcode to remove the ultrasonic noise inherent with DSD recordings. The telltale “purple haze” is easily seen in the spectragraph. There are other downloads on the Design w Sound website at 384 kHz…and the audio stops at 25 kHz.

But Kent also mentions that he has applied some “limiting” to his recording. Do we all know what limiting is? It is a heavier version of dynamic compression that is usually used by radio stations and mastering engineers to brickwall “limit” the amplitude of a recording.

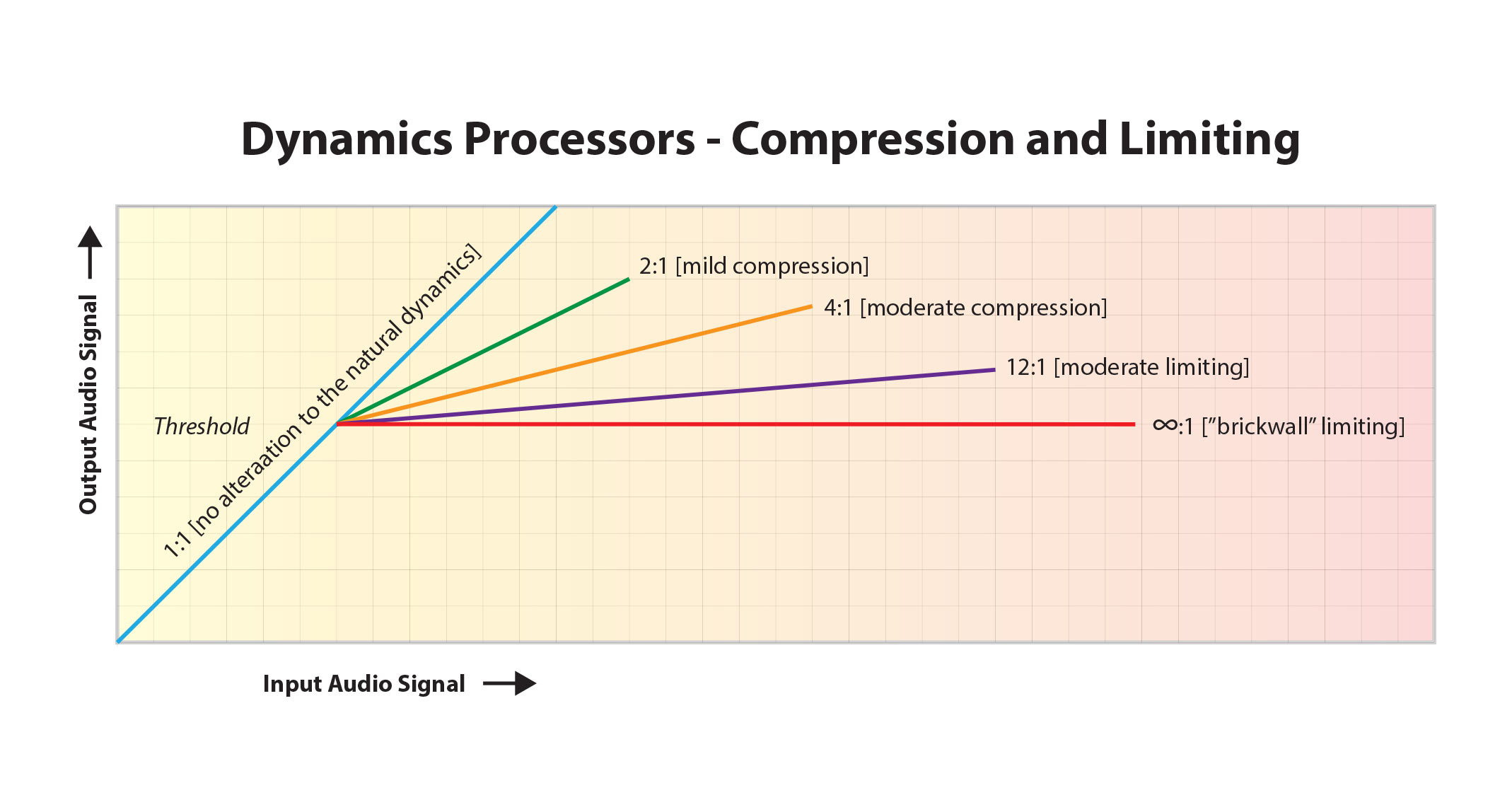

Take a look at the graph below. It shows the input and output of a typical dynamic range signal processor…a device that allows us engineers to get control of the dynamics of a particular track. Compressors and limiters can be applied at any stage of a recording. Notice that the blue line represents the natural one to one transfer that an ideal recording device would provide. Due to limitations on electronics, bit depth etc., engineers can choose to “compress” or “limit” the dynamic range of a signal. The higher the ratio of the transfer function the harder the processor reduces the real world dynamic range. This increases the apparent loudness of the track. Is that what we want from an audiophile recording? Do we want the engineer (usually a mastering engineer) to alter the natural dynamics of a recording to their own personal taste or would you rather trust the musicians to get it right during the performance? PCM digital recording and the rest of the electronics in the production chain can accomplish real world dynamics…finally. It’s up to us whether to provide that level of range on our releases or not.

Figure 2 – Dynamic Range Processing – Compressors and Limiters (Click to enlarge)

As I read the tech notes by Kent Poon, I wondered what would possess a respected audio engineer and record producer to consciously “limit” the natural dynamic range of a project by “2 dB” (remember he says limit not compress). Is this a version of “mastering light”? There must be a reason why he felt the track needed to be limited by that small amount. He then goes and asks that you increase the volume of your preamplifier by 4-8 dB so that the “average” value or RMS volume is nearly the same as you would experience from a heavily mastered track. I do agree that audiophile recordings usually need more amplification than typical tracks.

The technology that engineers have available today means that we don’t have to limit or compress our recordings unless there are creative or musical reasons to do so. I don’t see those reasons applying in this particular recording.

BTW When I read a post on another computer music forum that says we don’t need any more than 70 dB of dynamic range to capture a music performance, I have to question what world that listener lives in. There are a lot of sound events that exceed that number.

Mark, if you were compiling a recording, and you discovered that preserving the natural dynamic peaks required an average level of -30 dB, would you leave it unmolested?

How many domestic replay systems would be able to cope with the peaks if the average level was set to a satisfying volume? Conversely, if level was set at home based on coping with the peak volumes, how satisfied would the customers be with the average volume during playback?

Grant, I understand your point but I don’t touch the natural dynamics of any recording that I’ve made. I have done any strict analysis of our releases and the average loudness level but I can report that I haven’t had anyone comment that they’ve had difficulties.

I did get a review in TAS for our Bolero recording stating that it had “too much dynamic range”. I remember sitting at the console during the mix and thinking to myself, “Should I just nudge the snare drum solo at the beginning?” I didn’t touch the natural arc of the piece. It does take a good quality system to play it back but isn’t the whole point that we can record and reproduce real world dynamics in a 24-bit PCM digital world?

I certainly think so…and our customers seem to be as well.