More Detail at All Levels

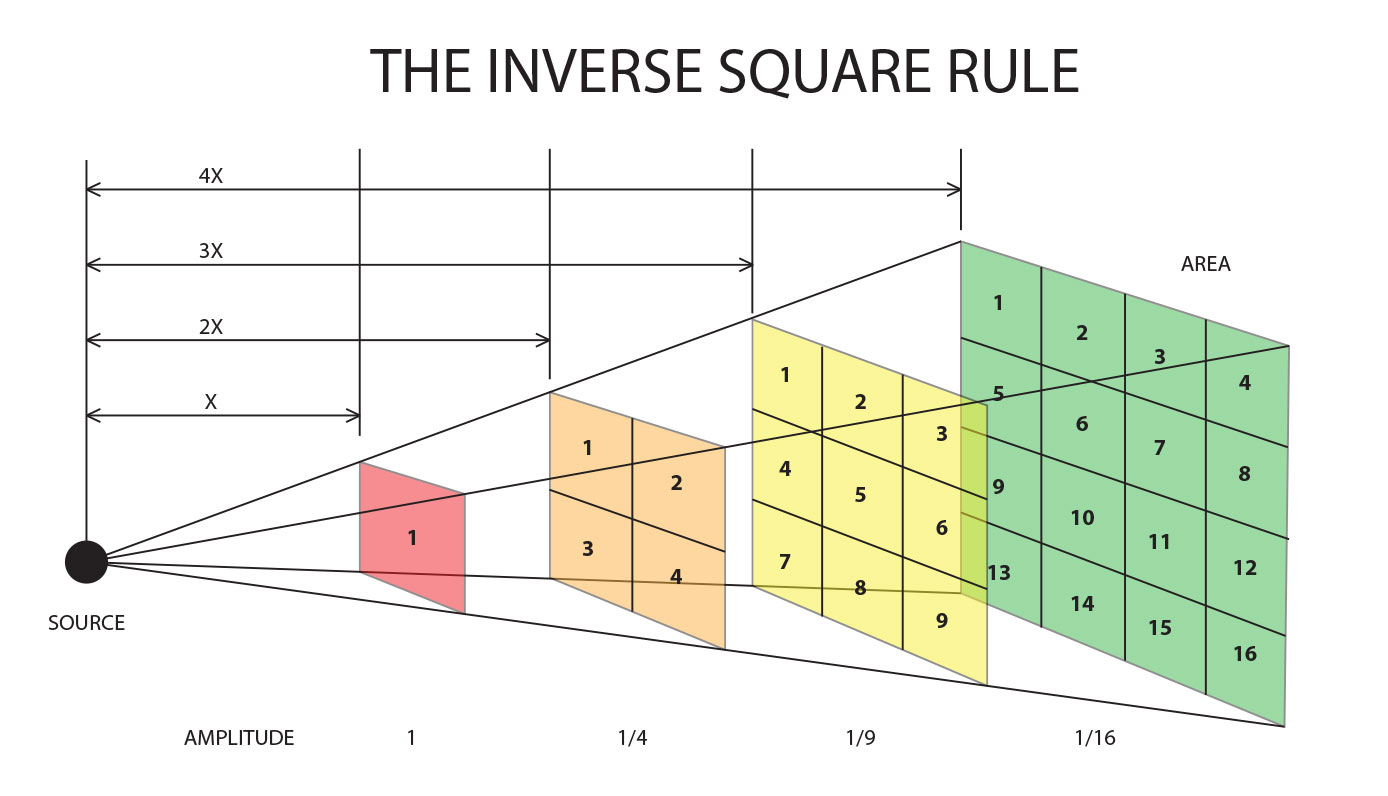

The amplitude of sound diminishes according the inverse square rule. That mathematical formula states that if you double the distance between a sound source and receptor (such as a microphone or your ear), there will be one quarter of the original energy present. If you move four times as far away then the sound level will be one sixteenth as much as it was to start. This is also true of light energy.

Figure 1 – The Inverse Square Rule (Click to enlarge)

There are all sorts of musical details generated by performers and their instruments while they play. It’s not just room reflections, echoes and reverberations that need to be captured during a recording. How about the grittiness that happens when a string player first draws their bow across a string before the string actually starts to produce a tone? Or the finger noise that happens when a guitarist moves quickly up or down the fretboard of their instrument? These are part of the aggregate sound.

If you’re a musician, you already know the intimacy of playing and instrument AND the many subtle and not so subtle noises that emanate from your instrument. If you’re not a musician, perhaps you’ve had that rare pleasure to sit very close to an acoustic performer as they strum and sing. I highly recommend that you visit a music school and search out a bassoonist. In close proximity, there is more air noise coming from the keys and holes on that instrument than there are musical notes. But when the bassoon does their thing in the middle of an orchestra and you’re sitting 40-100 feet away, all of those “extra” sonic details meld into the overall sound.

So if capturing and reproducing ALL of the sonic details of a performance is important, then the standard procedure of placing a few microphones many feet from the source needs to be rethought. When I started AIX Records, I considered that very thing. As a result, all of my recordings…including the ones I’ve done of a full 120 piece symphony orchestra…were done with stereo pairs of microphones placed close to the sound sources. Recordings of symphonic music are NOT done this way and as a result they strike me as distant and unfocused. But Hollywood film scores are done using multiple microphone techniques (they don’t use stereo as I do…oh well) and millions of people have been exposed to “close up” orchestra sounds.

For smaller ensembles, I place an ORTF (a stereo microphone techniques that places two identical mikes about 10 inches apart at a 110 degree angle) pair just inches from the front of an acoustic guitar or the speaker cabinet of an amplified guitar. If you take a look at the video of the Mozart Clarinet Quintet recording that I did a few years ago, you’ll notice a stereo pair of microphones above each of the upper strings and a stereo pair close to the cello and clarinet. You can bet that those mikes are getting a lot more “detail” than a simple pair of 5.1 array of microphones 30-50 feet away (remember the inverse square rule).

Figure 2 – The Old City String Quartet – Horn Quintet – notice the close stereo miking.

It’s easy to dial up the ambient microphones that I place some distance away from the stage and minimize any obnoxious “details” but it is impossible to put details back in if you don’t have microphones up close when you’re making a recording. No amount of compression or equalization is going to fabricate sounds that weren’t captured in the first place.

I love the sound of being close to a guitarist as they pick or strums or a piano as a skilled performer pulls all of the nuances of the instrument out for the audience. I put microphones right up close to the strings of a piano as well…and pianists and reviewers have said that the sound is “the best they’ve every heard”.

Would you hold a conversation with someone at a distance of 30 feet or more? Why do we insist on listening to recorded music that way?

The easiest way to understand the “inverse square law” is that the radiant energy is spreading out to cover a larger area as it travels so that at twice the distance, the area it covers is twice as wide and twice as high, meaning that its energy is being spread across four times the area (that this is actually an approximation is made clear by visualizing that the area being covered at a given distance is really a segment of a sphere).

The “binaural” versus “close-miking” debate goes back to the earliest days of stereo, and the only justification for only binaural miking in the middle of the audience is to reproduce the experience of going to a concert. But what about the experience of playing in a concert?

When movies were first made of what had been stage plays, the model was much as in binaural recording – the screen was the same shape – three quarters as high as it was wide – as the proscenium of a theater (an aspect ratio known as “Academy” and followed by television until a few years ago) and plays were filmed.

That didn’t last long, and dramatic close-ups soon led to location shooting. No one insists that the experience of going to a movie should reproduce the experience of going to a play, Film is an independent art form.

The same should be true with recorded music. Sure, you want to capture the ambient sound of the room, but not at the expense of losing the ability to focus close-up on the musicians. This argument can also be used to justify “assembled” recordings, which is what most recordings are today, but what AIX is doing is to use the best of both approaches to enable a close-up experience of a live performance.

Close-up stereo pairs on instruments enables close-ups that don’t sound “flat” (viz today’s “3D” movies, many of which are shot in 2D and turned into moving “pop-up books.”)

Thanks Phil for the comments…I think you get the idea. The particulars of recording are determined by the engineers, artists and producer. There are lots of way to approach a project. I’ve made my choices and the results are compelling for me and lots of others.

They’re compelling for me as well. My “stage perspective” download from iTrax of The Steve Huffsteter Big Band’s Gathered Around is one of my go-to recordings to demo my 5.1 basement theater’s audiophile capabilities – after I warm up my visitor with something from Guitar Noir by Laurence Juber – showing the range from subtlety to power that’s available.

Unless you are a musician, you don’t listen that close-up. We normally listen to music in a hall at some distance from the performers. Do we really want to hear all those non-musical noises?

Don, that’s exactly the point….because of technology, we now have the option of hearing music close up. If it’s unpleasant to you, simply switch to the “audience” perspective. The intimacy of a close recording is a real treat. Download the examples from the FTP and see for yourself. The “noises” are not an issue…they are part of the music making…but you’ve never heard recordings that present before.

I’ll write more on this…but welcome comments from anyone that has heard these things both ways. I’ll prepare a set of files in 5.1 audience and stage and upload them to the FTP site.

Mark,

Thank you for the blog posts; I am learning a lot from your blog. Thank you for redesigning iTrax in order to list the provenance of files. Thank you for setting up an experiment that will prove or refute the contribution of ultrasonic frequencies (out to 48 kHz) to accuracy. Thank you for reaching out to well-known musicians (Herbie Hancock) inviting them to record in a chain that contains no weak links (no bottlenecks); I and others want to hear the results and share it with the world. Thank you for being scientific, fair-minded, and friendly; it makes your blogs and comments a joy to read and learn from. I’m reading your blog daily and planning the evolution of my system; I plan to eliminate all the bottlenecks so one day I can achieve flat response from 20 Hz to 48 kHz from end-to-end and one day truly hear what it is you are recording. I like what I hear today from the Laurence Juber, John Gorka, and the New Jersey Philharmonic…I can’t wait to hear it without having distorted or truncated the natural full set of harmonics (out to 48 kHz).

The world of recording and playback you envision makes perfect sense to me and I believe it will be fully satisfying. We’ve all known quality is king, but going decades without an indisputable definition of quality has resulted in waste for the music recording industry, consumers, and manufacturers alike. Scientifically showing what matters and how it matters will free up makers of equipment and recordings and consumers to focus on improvements that will truly satisfy in a long-lasting way. I think consumers will flock back to buying equipment and recordings if the definition of quality is scientifically proven and they have an unambiguous way to identify recordings and equipment that will give them the quality they seek.

Mark, you seem to be the only person making this happen. If we can help you in any way, let us know!

Alex S

Thanks Alex, I really do appreciate the encouraging words. The majesty and mystery that is music deserves a continued effort to “do the right things”…it can’t be all about making money. I’ve been working on the iTrax.com new design…I’ll put up some pages to allow readers to comment.

I commend to you this article by violinist and critic Robert E Greene, which does not encourage the point of view you are promoting in today’s post, Mark.

http://www.regonaudio.com/HighRomanticism.html

His key point being that instrumental tone changes as the microphone approaches, and that for classical music this is catastrophic.

Thanks Grant…I have read this article previously and have heard Robert speak on his preferences and opinions. I disagree with his “right and wrong” assessment of recording orchestras of any period. The performance practice of the Baroque period vs. that of the late Romantic period are undoubtedly different. However, the proof is in the listening…when I played the Respighi “Pines of Rome” for Zdenek Macal (the music director the NJSO), he was astounded! He told me that this was the first recording that he had ever heard (of his conducting or others) that actually sounded accurate to what he intended…both sonically and artistically. That was a long time ago. I know that piece is a 20th Century master work but it uses a very large orchestra.

Richard Hardbattle wrote a review of our Bach Brandenburg recording with essentially the same comment. He had heard dozens of different recorded version of the works but mine was the first time he felt there was tonal balance and depth in the sound.

It is a matter of taste…but the feedback that I received from musicians (including most of the faculty of the Colburn School for Performing Arts…who can here on the recommendation of a violist…because he was so over the top about the sound we got!)m is uniformly positive. They get it.

Robert is a traditionalist and is welcome to his opinions. The sound and emotional/intellectual involvement that I get from my recordings is shared by many…and they are amazed at the experience. Technology trumps tradition in this case.

Thanks for the heads up. It is a worthwhile read…I just disagree with his position and his conclusions.

I should write a more focused essay on the topic. As a composer, musicians and recording engineer, I think I have something to contribute in this area.

I commend to the “traditionalists” Flanders and Swann’s “A Song of Reproduction” (about the early days of stereo) from At The Drop of A Hat “So we sharpened fiber needles, to make it soft again!

Of course as soon as I hit ‘Post Comment’, I regretted the word ‘catastrophic’: it should have been ‘damaging’.

Your reply to me is most illuminating. Another day, another lesson. I would appreciate the more focused essay: as it stands, I see a lot of logic in Greene’s observation about tonal balance at the intended listening distance being strongly formed by indirect sound, and close mic techniques losing this and hence seeming sharp and detailed in a manner not intended.

Hi Mark,

Very interesting and educative reads, daily.

I have question on the recordings/mix itself (may be for a different topic of your pieces); With the mikes so close to the performers, how do you get the optimum stereo picture? The sounds will overlap and the sound of the cello will also be heard on the violin mike.

By placing microphones close to the instruments rather than recording the entire ensemble with a stereo pair place some distance back…you actually get more ability to separate instrumental colors. The overlapping or “dovetailing” of the instrumental groups can create a seamless blend of the entire ensemble. Read the next installment about this issue.