Presence: Good or Bad?

For about a year back in the 1980’s, I worked as a “boom man” for production sound mixer Mike Denecke (aka “Father Time”, the late inventor of the timecode slate among other clever film industry devices). He had been hired as the production sound mixer for a film starring John Cassavetes called “Love Streams” and because it was low budget production he needed someone who would work cheap. I was his man. He taught me the basics of handling a boom, how to avoid getting the mike or its shadow in the shot and how to use radio mics. The first few days were hell, but I got the hang of it pretty quickly. We worked together on films and commercials for the better part of a year.

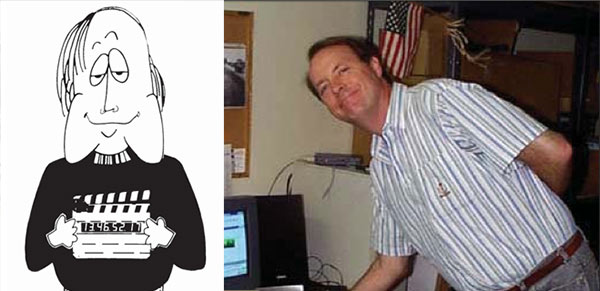

Figure 1 – The late Mike Denecke, inventor of the timecode slate, musician and one of my mentors. We once drove cross country and communicated using only Morse Code through the entire state of Nebraska…no joke!

For those of you who don’t know what a boom person does, here’s a brief description. You hold a microphone on the end of a long boom right over the heads of the talent during a film segment to capture the dialogue. You have to avoid dipping the microphone into the field of view and causing visible shadows anywhere in the shot. But the most important thing that you have to achieve is good sound of the actors in the scene.

Just what is good sound when it comes to doing location film sound? It means you have to point the “shotgun” (a very directional type of microphone) mike directly at the mouths of the actors to get the right amount of presence. This is the boom operator’s most important task during a take. You’re also part of the rehearsal because you have to learn the dialogue to know when to rotate the microphone from one actor to another. If you’re late in making any transition, the production mixer will call you on it. Their job is to make sure that they capture the best possible sound. If you miss pointing at the source of the sound, the sound will lack presence.

Here’s what it sound like. Imagine you’re having a conversation with someone at a party. You’re standing reasonably close to the person and can understand what they’re saying because there’s a direct line from the source of the sound and your ears. However, imagine if the other person turned to one side while continuing to talk. You would notice the loss of “presence”…and would most likely have to concentrate a little harder to hear what they were saying. The same would happen if they were wearing a mask or holding a fan in front of their mouth.

Presence is a quality of sound. It is a directness and clarity that only comes by having your ears or microphone(s) in the right position in relation to the source. It is also directly proportional to the distance between the source and your ears.

Recording a musical instrument or an ensemble can be accomplished from a distance with just a couple of microphones…OR, as I’ve been advocating…it is possible to use multiple stereo pairs of microphones very close to the sound sources and then pan them within the stereo or surround field. Using the traditional approach results in a very blended, unfocused and “flat” sound…this is how you experience most classical and jazz recordings. Sure traditional stereo recording and playback does infuse a track with some sense of space and depth but it pales in comparison to the intimacy, presence, detail and depth of a close up recording. Using stereo pairs of microphones rather than single point sources enhances this even further. This was a large part of the success of Windham Hill Records…they placed mikes very close to the sources.

Presence is a big part of the overall sound. If you want to feel as if the players are in the space where you listen, then you need to consider that the speakers become the sound source or replacements for the instruments. This is method that I’ve explored over many years and have used for all of my AIX Records projects. Like it or not, the sound is dramatically different than virtually every other recording I heard.