Different Masters at 96 & 192 kHz?

The “Father and Son” tune from Cat Stevens’ “Tea For the Tillerman” reveals some additional issues with the new world of high-resolution digital transfers of recordings that were originally made using analog tape. I’ve already pointed out that there are numerous clipped samples on this track. But I also compared the 96 kHz/24-bit PCM file to the 192/24-bit version and discovered that they are not the same. I would have thought that the different sample rate wouldn’t affect the amplitude contour across the frequency spectrum…but it does.

Increasing the sample rate of PCM digital files does increase the potential for additional high frequency information AND make the filters used in transitioning from the high frequency musical material to the Nyquist frequency easier. But I think of PCM digital files as “boxes” defined on the horizontal axis by the maximum frequency range and the vertical dimension as the amplitude range. The box gets bigger as the sample rate and word lengths increase. I have never thought that the mastering process discriminated between these two high-resolution sample rates. But it seems that the Cat Stevens track proves otherwise.

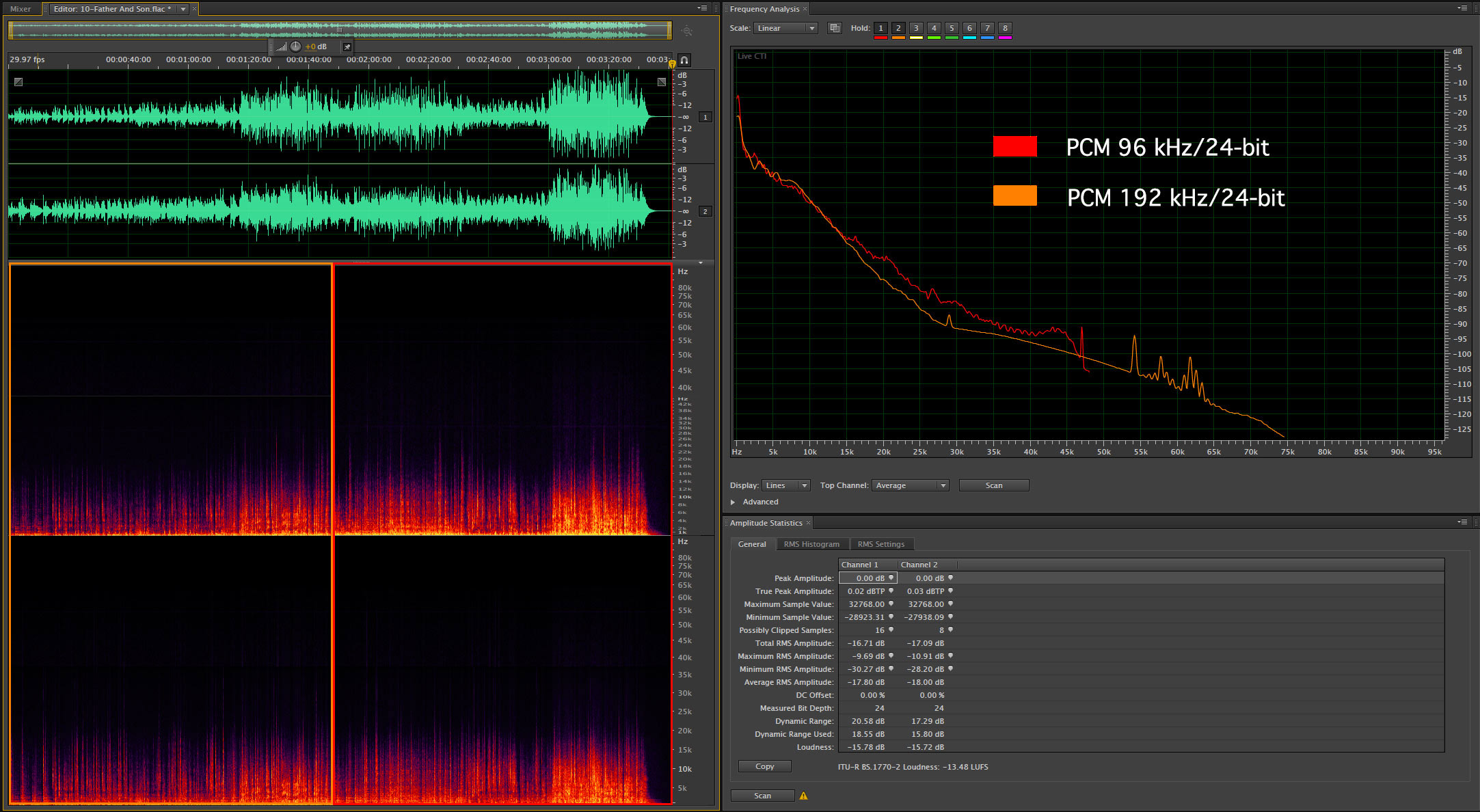

Take a look at the spectragram that I created of the “Father and Son” track. The left half of the plot shows BOTH the 96 kHz AND 192 kHz versions. Given that this recording was made using analog tape (a 3M 56 16-track 2 inch machine with Dolby A Noise Reduction), there is absolutely no need to make a transfer at 192 kHz. As you can see there are no frequencies above 48 kHz…the maximum possible with 96 kHz. The right hand side of the display shows that, in fact, they used a Low Pass Filter or LPF on the output. This may have been done to remove any chance that the bias frequency might get into the digital transfer.

Figure 1 – The spectragram of Cat Stevens’ “Father and Sons” at 192 and 96 kHz [Click to enlarge].

The interesting thing about the orange and red lines on the right hand graph is the increase in high frequency information above 15 kHz in the 192 version. It’s not there in the 96 kHz trace. Why not? Is it possible that the analog to digital transfers was done twice, once at 96 and then again at 192? Well, quite possibly yes. The transfer was done using an MSB Technology ADC. It is unlikely that the studio owned two of these units since they are expensive. My guess is that they did the transfer at one sample rate and then rewound the tape and did another pass after switching the sample rate to the other value. Nothing else should have changed.

Then the mastering engineer must be responsible for the noticeable elevation of the high frequency range in the 192 kHz master. The mastering was done to each of the two transfers separately. The EQ and dynamics adjustments that Ted Jensen made to the digital transfers were not identical it seems. So the two files are different.

Another possibility is that they did a single transfer at 192 kHz, did the mastering and then created two outputs…one at each of the target sample rates. This would have insured that the two versions would be identical with the exception of the sample rate. And that’s what consumers want. Are there any downsides to doing a sample rate conversion from 192 to 96 kHz? Not really. The SRC (sample rate conversion) algorithms have advanced well beyond audibility…especially when going from 192 to 96. The process simply eliminates every other sample.

I discovered this issue by examining the very first track of this album. I just have to wonder what other things are happening to the files we’re purchasing again…for premium prices.

Merry Christmas everyone!

“Another possibility is that they did a single transfer at 192 kHz, did the mastering and then created two outputs…one at each of the target sample rates. This would have insured that the two versions would be identical with the exception of the sample rate. And that’s what consumers want. Are there any downsides to doing a sample rate conversion from 192 to 96 kHz? Not really. The SRC (sample rate conversion) algorithms have advanced well beyond audibility…especially when going from 192 to 96.”

This was my thought, with the SRC algorithm “smoothing” out the overtones for the 96kHz file as a “feature.” Kind of like DNR when encoding a video file from a higher-res master…?

Anyway, hope all is well Dr. AIX! Cheers, Felix

Hey Felix…happy holidays. Thanks for the comment. I’m not sure the differences are deliberate. I believe they did two transfers and modified them differently.

Mark,

I am confused by this. First isn’t the orange the 192kHz and the red is the 96kHz? If that is so, then the elevation above 15kHz is on the 96kHz version, not the 192kHz version. Another thing that I notice is that the slight blip at 28kHz in the orange plot is not present in the red plot. If that was an oscillation in the path, then I would expect it to be in both plots if they were from the same transfer – wouldn’t you?

Thanks and have a great show!

Blaine

Blaine…you’re right. I switched the colors when I put the annotations on the plot. I fixed it this morning. You got the whole point of the post…these transfers or new masters are unique. The question is why?

I guess the idea of “Mastering” escapes me in the digital age. I believe that when lacquers are cut for vinyl, there is something to be gained by reducing bass and removing it from the difference channel that can compensate for vinyl limitations and lesser quality playback devices; i.e., cheaper turntables/cartridges, etc. I remember a James Taylor LP (Gorilla?) that was always returned to the record store because it skipped on inferior playback equipment. But in the digital domain I just don’t see the need for mastering at all – the source the way the artist and producer wanted it. Even the cheapest CD player can use all 16 bits (well, most of them). Does the mastering engineer know better? Maybe I don’t understand what mastering is…

Blaine