Mastering and Loudness: Part II

I had to do a follow up post based on a couple of comments and some discussions I’ve had about the whole dynamic range component of music listening. I listened to the most dramatic section of the “Mosaic” tune. It’s near the end when Laurence and the ensemble start leaning in on their instruments. From about 30 – 40 seconds into the final section, he starts playing louder and puts more energy into his playing. This is what music is all about. It’s what makes music sound human and alive. If the ideal is to capture/deliver real world dynamic range AND we finally have equipment that is capable of accomplishing that feat, don’t we want to be able to hear it without any additional dynamics processing by mastering engineers? I certainly do and that’s why I do not master my recordings at all. At the very least, I want the option of being able to choose how much dynamic compression I want for my music.

I’ve mentioned before that The Absolute Sound magazine faulted my recording of the Ravel “Bolero” because it had too much dynamic range…imagine that. We finally have technology that allows us to meet the real world dynamics of one of the most dynamic orchestral selections ever composed and their reviewer believes I should have mastered that natural loudness progression out of the piece.

For today’s discussion, I have modified the mastering that was done on the Mosaic piece. Rather than the entire piece, I chose to include only the final 1:30 of the piece. This is where the dynamics are most apparent…very obvious, in fact. There are individual files that have a range of mastering applied to them…from the original non-mastered file to an “extreme” version that sadly is representative of what we get with most CD and iTunes releases. Remember louder is always better (just kidding).

Each of the files has had its amplitude adjusted so that the RMS (think of this as the mean or middle level) values are identical. That means that I have tried to make them sound the same with regards to loudness. Of course, this is impossible because of the progressive nature of the each mastered file. The “extreme” mastered section, which is the last in the sequence, is dynamically very flat. I had to reduce the overall level about 12.5 dB to make is match the RMS value of the uncompressed version, which was not altered at all. However, some sections of the uncompressed version are quieter and some sections louder than the one that is extremely compressed.

I have placed these files on the FTP site in the same Mosaic file folder as yesterday (Mosaic Mastering Comparison 140630). You will find the final section of the tune in 5 different mastering versions AND you will find a file that contains all of them strung together from no compression to extreme. If you open this file and jump between the sections, you should hear a huge difference between. Remember, this comparison has nothing to do with ultrasonics or frequency range. It’s all about the mastering of a track for sound and dynamics. Which do you prefer?

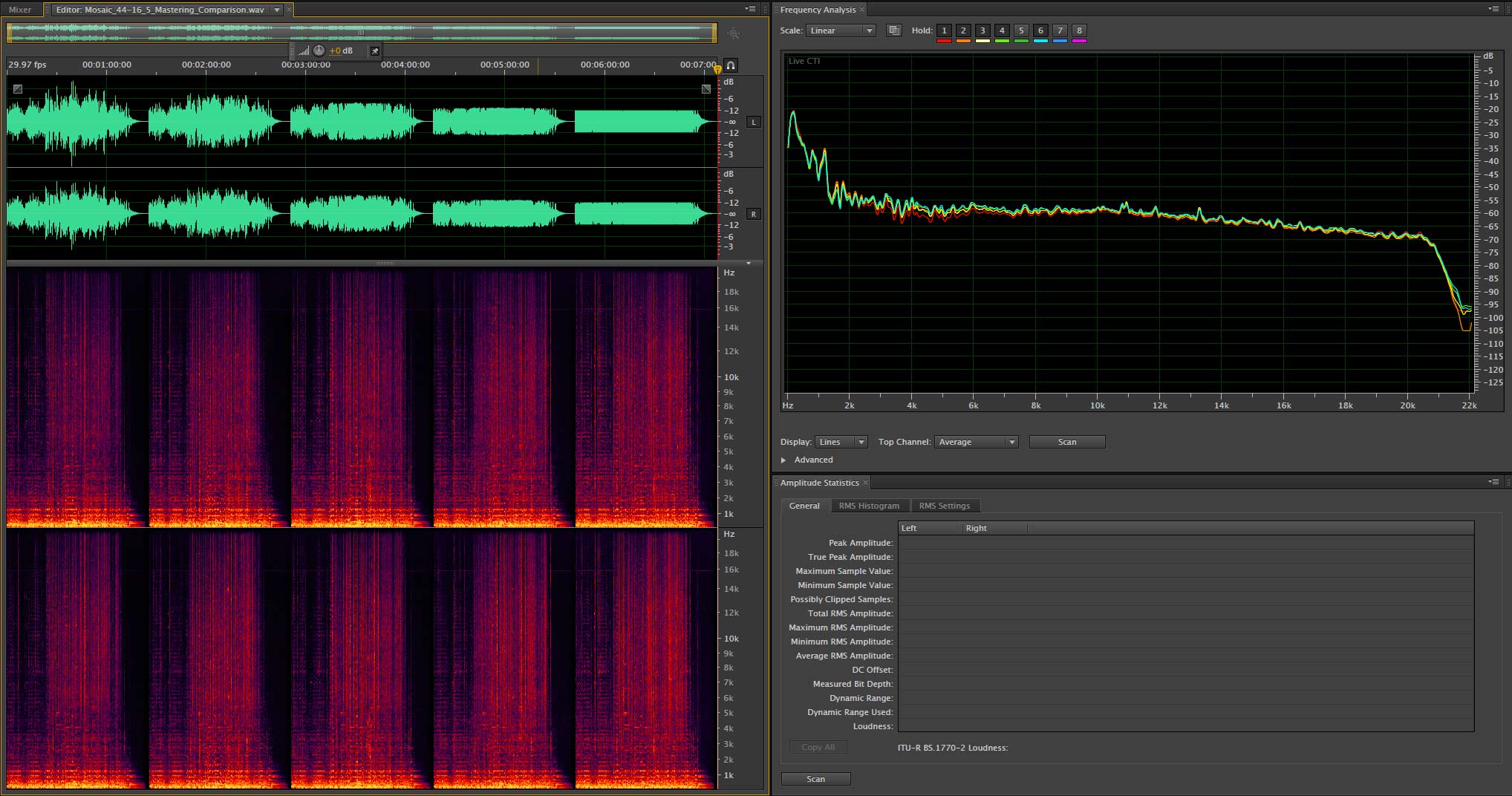

Here’s the spectrogram for the assembled file (Mosaic_44-16_5_Mastering_Comparison.wav):

Figure 1 – The spectra and amplitude waveform of five progressively more compressed versions. [Click to enlarge]

Here’s what you should be looking for in this graphic. Notice in the light green area at the upper left hand corner, the amount of vertical variation in each section. In the version that has not been mastered there is tremendous variation in the vertical or loudness contour. Then compare that to the extreme compressed version at the right…this is a “brick”. There is not variation in the loudness from the beginning to the end. Listen to each example. There is virtually no musical sensitivity in the “extreme” mastered version…but sadly this is how most newly released music sounds.

It’s easy to master the dynamics out of a selection of music, but it’s not easy to put it back in.

More coming…

I didn’t listen to your demos but, I wish to say that dynamic range must, in most cases, be reduced in order to accommodate real world listening environments. Of course, how much reduction, if any, is key. I’m sure you realize this but, I believe we should have a discussion regarding, in simple terms, what the differences are between a particular recording space and the average expected playback environment.

In a typical commercial pop recording, where most of the instrumentation does not exist in real space, the possibility to reproduce the dynamic range in the home is more doable and then its just a mater of “Volume-Control” change. An acoustic performance is quite different. If we have a small performance space, perhaps a room that is say 20 by 30 feet, we can not expect to have that same room crammed into a conventional living room without further consideration. Sure, its a matter of scale (the volume control) but, fortunately to a degree, the speaker systems will by default provide dynamic limitations since the speaker system has a more restricted practical dynamic range compared to a first class DAC where you have, electrically, a possible 110 or more dB of range. Twenty or thirty dB of useful listening range from a speaker system would be a common maximum that most environments/people could handle. A speaker system that has an average 87 to 90 dB spl at one watt/ one meter on axis usually will be rated no more than 105 dB or so maximum. Even if rated to output say 115 dB, we’re still talking a major difference in dynamic range even compared to the average electronic playback chain so, dynamic compression is the end result of acceptable playback conditions.

Regarding compression in the recording, it is sometimes necessary. I agree that in general, compression in the recording is over used. Dynamic range is only part of the consideration as a full scale orchestral piece can not transfer into a living room, not just due to dynamic range but, also the entire venue’s space signature is also missing unless everybody has a multichannel advanced, industry standardized playback device capable of recreating the original environment but, scaled down to accommodate the obvious difference between the two environment’s safe maximum spl.

I’d appreciate your comments because you are directly involved in providing us with a practical recording that can meet a balance between the real and the facsimile.

Thanks in advance.

Having the ability to change the dynamic range of a given file is something that can be easily built into playback devices. In fact, we have had loudness controls on A/V Receivers for years that modify the dynamics for music and movie soundtracks. I agree that dynamic range and controlling it is important for practical and creative reasons.

I’m not so sure that playing orchestral music in my living room or my moderately sized studio misses the mark with the idea of recreating the experience of a big ensemble performance. I love listening to the “Pines of Rome” in my room or even on a set of headphones.

Too much dynamic range ? Sounds like a statement out of Washington !, Mark, once you get the right ears to eventually take a listen, hopefully someone will wake up.Nobody is on the same page within anything anywhere it seems.i cant imagine how frustrated you must be, im so darn frustrated reading on your ventures.Reminds me the battles at the shop, try to make things much better and the so called experts have it all wrong.keep the faith Mark, we appreciate your drive for excelence

It’s very challenging to see how much misinformation is being spread around. The HRA definition is a prime example of a misguided effort. It is so watered down as to be meaningless…but I’m getting push back from the parties responsible for not “going along”. Argh.

As a LISTENER, and a very amateur musician, not an engineer, I always prefer to hear a real live performance, though I certainly listen very very happily to lots of recordings. I have spent thousands of hours in concert halls, clubs, and homes listening to orchestras, jazz, folk musicians, chamber music, etc – a wide variety of acoustic and amplified music. I respect and am grateful for the efforts of thoughtful engineers and producers to create recordings that are respectful of the intentions of the artists and musically satisfying.

After decades of listening I no longer have the illusion that a recording might ever “reproduce” the aural experience of an actual performance. The idea is absurd. But there are wonderful performances “captured” on recordings, some of which are beautifully recorded, some of which are adequately recorded to convey the immense excitement of the music, despite serious audio imperfections.

I strongly support the effort to produce recordings with as little processing as possible. There are times – as in listening to the radio broadcasts of the Met Opera – when the compression used is appalling – it seems to have been designed for radio communication between military units under heavy shelling. But when recordings with a much lower noise floor became available in the CD era I noticed that – particularly with orchestral recordings – the higher dynamic range that engineers were reveling in very frequently created recordings that, when listened to on a good system in my living room (not a laboratory-quiet environment), presented low-volume passages that were, for musical purposes, INAUDIBLE along side high-volume passages that were physically painful to my ears. I have attended many orchestral concerts of music with wide dynamic range and I have very rarely felt physical pain in my ears and never been unable to fully hear the soft passages. This phenomenon may well be accounted for by limitations of speakers as mentioned by philmagnotta – and is undoubtedly affected by many other circumstances – but, as of now, we have to live with those limitations, and engineers can choose to take them into careful consideration – or not.

So, from my ignorant listener’s perspective, the idea that because there is no compression in a live acoustic performance there should also be none in recording is nothing more or less than an rational ideal not entirely grounded in real world experience. It isn’t a crime, it’s a dream, and it’s a good dream.

I must say I’ve listened briefly to some of Mr. Waldrep’s online samples and I think they sound great: there’s a lot more to recording than whether or not you use compression.

Thanks to all engineers and producers who are committed to staying out of the way of the music!

Making recordings is a challenge. And while my personal goal is not to recreate a live event, I think we can come pretty close with certain approaches and technologies. There’s room for live music and recordings of all sorts.