Preserving the Past

This is the final installment of my thoughts on the article in the Wall Street Journal on “Hi-Res Audio Hijinx” by Wilson Rothman. His bottom line? “The trick is knowing that not all hi-res albums are created equal.” To that I would add, that there are even fewer hi-res albums that are actually hi-res. The final section of his article says it all. What’s happening in the labels is decidedly not the release of new high-resolution audio projects. They are preserving the past.

Wilson’s description of the “hi-res versions of albums recorded decades ago” discusses the problems that record labels have ensuring that their vast catalogs of analog masters get brought properly into the high-resolution digital future. They’ve all got to deal with this. There are large temperature and humidity controlled vaults that house the crown jewels each label. There is a very critical step in getting from the analog tapes to a PCM, high-resolution digital file.

What is happening at Blue Note, ECM, Warner Brothers Records and all of the others is the laborious task of future proofing the catalogs of analog tapes. In the case of Blue Note, which is run by a fellow Detroit refuge and acquaintance Don Was, they’ve been transferring older analog master recorded prior to 1972 to digital. According to Wilson’s article Don is intent on doing these transfers for the last time.

But there’s a wrinkle in their approach, in my opinion. The goal of the new transfers was “to create as neutral a digital facsimile as possible.”

“That transfer, however, ‘doesn’t feel the way you remember the records feeling,’ said Mr. Was. The next step is to replicate the vibe of vinyl by applying subtle equalization and compression. Mr. Was and his team listen to the original vinyl records alongside the new mixes to ensure they are capturing that Blue Note sound. Only then is the album released for sale.” Wow, I’m surprised to hear that modifications are being done to sound of the analog tape masters in search of the “vibe of vinyl”.

This is another case of changing the “artist’s intent” during the final mixdown session to comply with a compromised format…namely vinyl LPs. Adding equalization and compression to the sound of the two track analog master is a wrong headed thing to do. Blue Note is going through such pains to get the very best transfer from the aging tapes, why in the world would they then apply sonic changes that are only required for vinyl LPs? Give me the raw transfer, please. The analog tapes are much better than a vinyl LP.

These labels have the responsibility to “preserve” the past…not color the past according to someone’s personal fidelity preferences. Audiophiles and music enthusiasts want the very best sounding files they can get. Steve Wilson had it right. When the final mixing session is over and the production team deems their work complete…there shouldn’t be any additional dynamic or timbral changes made to the tracks. Go ahead and change the order, set the gaps, establish the relative volume of the tracks but avoid anything and everything else.

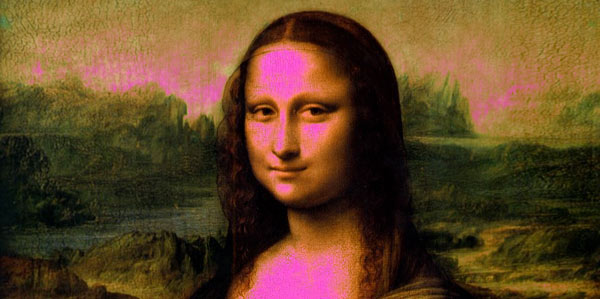

Imagine if an art restorer decided to change the colors of the Mona Lisa instead of cleaning it? That’s not preserving a masterpiece, it recasting it according to the preferences of the time.

“Imagine if an art restorer decided to change the colors of the Mona Lisa instead of cleaning it? That’s not preserving a masterpiece, it recasting it according to the preferences of the time.”

You are absolutely right, Mark.

Some decades ago, a few people tried to “colorize” black & white movies. Swiftly, they were sued because it was perceived as changing the original opus. I suppose audio is more subjective.

This gets into an area that can be complex. For example, if I were to get a hold of the multitrack tape of a classic album and remix it into 5.1, is that a violation of some sacred trust between the artist and his work? I don’t think so…

Changing the colours of Mona Lisa is one thing – that would be destroing the original piece of art.

Changing a piece of music in the mastering process is different, since they are working with copies of the original art.

And it would be ok, as long as we are offered the ‘untouched’ version as well – and we are fully informed about the origin of what we buy/pay for.

If someone likes the ‘changed version’, let him have it – I’ll take the ‘untouched!

Unfortunately, we don’t get to hear the originals…the folks at Blue Note have decided that will remain in the archive. I’m going to try to meet with Don Was and convince him to let me try a a test with one of the originals.

“Some decades ago, a few people tried to “colorize” black & white movies. Swiftly, they were sued because it was perceived as changing the original opus. I suppose audio is more subjective.”

That was sad, who wants to watch in black – white when color is possible. I watched a number of colorized films and enjoyed them very much.

The choice is good but the creatives might think otherwise.

replicate the vibe of vinyl by applying subtle equalization and compression… why oh why would anyone do this?? I mean seriously. What possible benefit could this have? I’m just scratching my head here. I’ve done enough tape recordings to know that yes the sound different to LP’s but that’s why we went to tape in the first place. Forcing a ‘format over digital’ is just wrong headed.

I will ask Don when I see him…I’m hoping to meet with him soon. I’m sure their justification is to match the sound of their releases during the age of vinyl LPs (which despite all of the insistence that there is a major revival still only accounts for 2% of recording industry revenue).

What a disaster. “Wow, I’m surprised to hear that modifications are being done to sound of the analog tape masters in search of the “vibe of vinyl”.

What we are now being told is that *vinyl* is ruining the sound of audio!

I blame you sound engineers. 😉

Don’t blame the engineers, they are being told what to do by the management.

I agree 100% on the Blue Note issue. Seems to me that they should archive the tape to preserve it as is. Not tweaked to sound like the vinyl. They can always do that later but not in the archival process.

Very sad and a completely backward approach. Why don’t they do it really right and add ticks, pops, surface noise, wow, flutter, and all the rest of vinyls flaws so history can sound as bad as it used to, FOREVER

I co-founded a group of several mastering facilities in the early 80’s which was very successful for more than a decade and then switched to sound restoration and long term archiving for an additional 10 years.

I can’t agree more about the role of the post-production engineer: his/her role is to respect the artist’s creation and the producer’s will.

The engineer has to use his/her skills to enhance the material he/she is working on to make it last for the next generation of listeners in respect with the original sound. Not more.

I think your Mona Lisa’s analogy is brilliant!

Carpe Diem.

Jacques

Thanks Jacques.

“These labels have the responsibility to “preserve” the past…not color the past according to someone’s personal fidelity preferences. ”

Sorry, but you are wrong. The labels have the responsibility to make the most money for their artists and shareholders, Period.

So the art of music is merely a means to making money? I don’t think you’d get universal agreement on that from the musicians and singers that create the stuff.

AMEN

Hello Mark,

Preserving the past by making the most accurate possible transfers from old master tapes is exactly what the labels should be doing.

But in far too many cases, they are not. An under-reported scandal in the record industry is that reissue production from the old analog master tapes is too often directed by persons lacking sufficient scientific knowledge of analog tape playback.

For proof of this, one could start with an up-close look at the tape machines the labels are using. Assembling a transfer chain with the critical hardware choices based not on science, but on someone’s personal nostalgia, is only a recipe for a sub-optimal transfer. (Does anyone really still believe that scrape flutter is not audible?) And reliance on perfecting a transfer later, through DSP, is probably deeply misguided.

Like guys with too many beers, talking pick-up trucks, a lot of veterans of the record industry seem insistent that they know all about tape machines. Yet test them, and you’ll uncover that many don’t understand (or can’t distinguish between) constant torque and constant tension, or force guidance and precision guidance tape transport designs. This fundamental tape machine design stuff matters because it turns out to be audible.

Fred Thal