Analog Tape

Recording on reels of magnetic tape started in the late 1930s in Germany. During WWII, German audio engineers improved the quality of recording by adding high frequency bias to the recorded signal. After the war Jack Mullin, a member of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, brought two Magnetophon recorders and 50 reels of tape home with him. With some financial assistance from Bing Crosby, Mullins and a local electronics company called Ampex went into the business of engineering and manufacturing reel to reel analog tape machines. The company supplied mono, stereo and eventually multitrack decks to studios and musicians during the 60s, 70s and 80s. Guitarist Les Paul was one of recipients and went on to pioneer multitrack overdubbing, which is a standard technique in the production of commercial music.

A reel to reel deck being used at an audiophile trade show.

Tape machines became popular as home recording and playback machines during the 60s and 70s. Audiophiles and enthusiasts continue to sing the praises of the format and purchase refurbished machines and custom transferred tape copies. Analog tape machines were also widely used in the production of motion pictures and television program until portable digital machines replaced them in the 2000s.

The standard format for analog reel to reel tape is 2.0 channel stereo on a 1/4″ piece of tape. Tape came in standard 7″ or 10 1/2″ reels and allowed for entire sides or even albums to be transferred from LPs or live sessions at 7 1/2 or 15 inches per second.

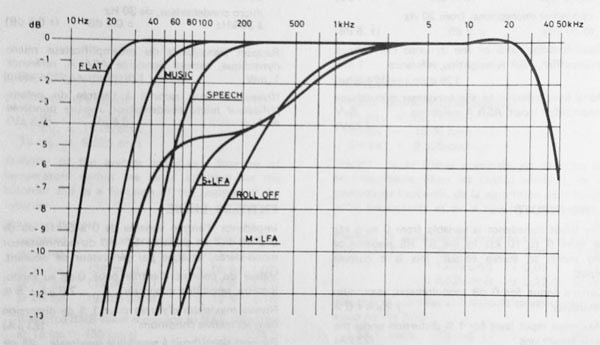

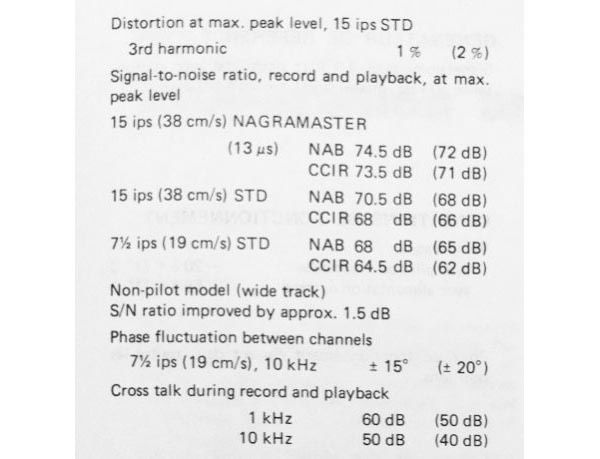

Tape is capable of capturing and reproducing reasonable fidelity. Typical signal to noise ratios for a master (first generation tape) range from 55-72 dB measured at the peak level and without noise reduction systems. Frequency response depends on the speed of the tape but reaches 20-35 kHz before diminishing rater quickly. The addition of an ultra sonic bias current (usually around 50 kHz) to the signal helps linearize the frequency response in the audible band.

Noise reduction systems such as Dolby A, Dolby SR or DBX were commonly used in multitrack studios to reduce the amount of hiss associated with the format. These system encoded the signal prior to the capture process and then decoded them upon playback. Careful calibration was required to maintain flat response curves.

Analog tape machines suffer from a number of challenges with regards to fidelity. The signal to noise ratio is pretty good on the original master tape but degrades with each transfer, the speed of the tape varies slightly causing pitch irregularities, multiple distortion types occur (modulation, magnetization etc), tape print through causes pre or post “echoes” or the tape can shred or be scraped from the Mylar backing over repeated plays.

Recent developments in analog tape recording have improved the fidelity. Custom machine builders are using wider tape tracks, higher speeds, better electronics and enhanced tape formulations. These machines are used in studios because of the particular tonal characteristics that they generate. The distortion is used to artistic effect.