High-Resolution: Does it matter? Part III

The content I reviewed in the first installment of this series was provided by Ethan Winer, a very familiar name to many audiophiles and enthusiasts. Ethan wrote a reference book called “The Audio Expert”. I have copy and value the information provided in his book. I wrote my own book to focus more on the production processes involved in making a great recording and methods that audio enthusiasts can use to improve the quality of their listening experiences. It turns out that Mr. Winer is a staunchly anti high-resolution audio. His stance is based on “if listeners can’t tell the difference, then the whole high-res business is a fake”. He has written repeatedly that CD 44.1 kHz/16-bit audio is perfectly adequate for “most normal music in most normal listening situations”. I agree. But audiophiles are not dealing with normal music in normal systems. We strive for the very best sounding music replication possible. And I believe that high-resolution audio does make a difference!

Readers of this blog might think that I would agree with Mr. Winer. I strongly object to marketing of standard-resolution audio as “hi-res music” and have tried for more than a decade to clarify the confusing offerings by “high-resolution” digital retailers — either as downloads or as MQA streams. They’re NOT high-resolution. The CEA, NARAS, equipment manufacturers, labels, DEG, and others have consistently pushed misinformation about high-res audio. But Mr. Winer and I disagree on the merits of producing and releasing recordings that were recorded using with sample rates and word lengths greater than CD specs — 44.1 kHz/16-bits. I acknowledge that with the exception of a few surveys, most investigations have failed to prove that humans can reliably distinguish between standard-resolution and high-resolution recordings. Some of the most well-known studies have been flawed. The well-know Meyer and Moran that equated the quality of CD vs. SACDs and DVD-Audio discs used only standard-resolution sources!

So I was surprised when the files offered for comparison on Mr. Winer’s site barely qualified as high-resolution. In Part I of this series (click here to link to it), discussed the first classical example. The spectra barely extends beyond a standard-resolution file and makes this file a poor example for comparing resolutions. I’ve heard from Ethan about this issue and he remains critical of my analysis. So I went back to the “pop” tune I acquired from his site. The illustrations below show the parameters of that file.

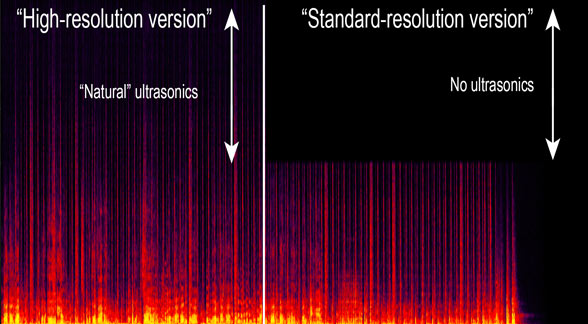

Illustration 1 [Click to enlarge]

This is not a good example of high-resolution audio. The ultrasonics in the “high-resolution” version actually increase in amplitude above 20 kHz — that’s not natural. And the “standard-resolution” or down converted version has “phantom” ultrasonics. Ethan told me that he added these to confuse people like me that would use tools to identify which file was which. But the added ultrasonics just confuse things further. This file also doesn’t contribute to a fair test. The dynamic range of 24-26 dB can be reproduced by less than 8-bits!

So I decided to analyze one of my own “pop” tunes to see what a real high-resolution files looks like. I used a track from Ernst Ranglin’s “Order of Distinction” Blu-ray disc. Alana Davis sings “My Boy Lollipop”, a classic track from 1962 (I remember the Millie Small original all those years ago). Take a look at a bona file high-resolution track.

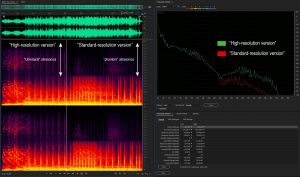

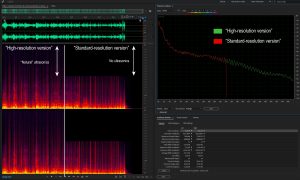

Illustration 2 [Click to enlarge]

This is what I had hoped to see when I downloaded Ethan’s tracks. Notice the natural diminution of the amplitude of frequencies as the get higher. They shouldn’t look blotchy and discontinuous as in the previous illustration. The sharp division between standard and high-resolution is evident at 24 kHz. The files are otherwise identical except for the ultrasonics. And a critical component that is part of “My Boy Lollipop” is the extreme dynamic range — above that of a CD (which tops out at about 93 dB when dither is applied). The dynamic range represents that uncompressed signals coming from the band and measures 96 of more! Would you be able to perceive any difference between these two versions? Probably not. But I would maintain that a rigorous study with bona fide high-resolution has not been done. So we don’t really know.

Anyone attempting to perceive differences between Ethan’s “pop” tune at standard and high-resolution specs wouldn’t have a chance. That was my point in analyzing the tracks I received from him. I think Ethan and I agree on the “normal” high-resolution music in the marketplace. But audiophile deserve more and I think that my files deliver it.

I’m in the earliest stages of working with a prominent mastering engineer on another test. We’ll see where it goes.

Frequency response beyond about 24 KHz is academic anyway, so a 48 KHz sample rate should be sufficient for music. OTOH, for those who believe that moving the sample frequency further away from the audio passband improves sonic performance, 88.2 KHz or 96 KHz should suffice. 194 and 384 KHz sampling is ridiculous though and all those sampling frequencies accomplish is larger (mostly empty) music files. What is important in so-called high-resolution sound is the bit depth. 24-bit does sound better than 16-bit and allows for more headroom and better resolution at lower volume levels. So, I do not believe that high-res is the ripoff that some suggest. Yes, like I said, the higher bandwidth is largely irrelevant (unless we are 12-year old girls, we likely can’t hear 22.05 KHz anyway, and since most audiophiles are middle-aged (or older) most of us can’t even hear 15 KHz , much less 22 KHz).

I agree that 96 kHz is more than sufficient to cover the audio band and give a buffer for better filtering etc. Using 24-bits for recording is critical but rarely delivered to consumers — even on audiophile tracks. The dynamic range is lessened through mixing and mastering. The potential is there for greater dynamic range but very few take advantage of it.

As for 24 bit sounding “better”, it’s only about signal to noise ratio, nothing else. If you don’t know why this is the case, here’s a very easy to understand explanation: https://www.head-fi.org/threads/24bit-vs-16bit-the-myth-exploded.415361/

So, I’m fuuuuuuully in favour of RECORDING at 24 bit, since you have more headroom to alter the volume levels during mixing. But I don’t think 24 bit makes sense as a consumer format. You have to add the background noise in your home to the dynamic range of the music you’re listening to. So, if you have 96 dB of dynamic range on a CD, and you live in a very quiet place with 20 dB background noise (it would be closer to 50 dB in a home in a big city), then you’re at a volume level of 116 dB at the loudest sound if the volume is turned up so you can just hear the most quiet sound above the background noise. I simply don’t think many, if anybody, would enjoy listening to music with those types of level differences. When I listen to classical music it’s bad enough, and I get annoyed turning up and turning down the volume, and that might be a recording with a dynamic range of 60 dB at best. Arny Krueger measured the dynamic range of a lot of classical CDs, and the highest he ever came across was 85 dB. Who would want to listen to music at home at a volume level of mostly 116 dB?!

Just to put things into perspective, I think it’s worth looking at this chart of volume levels:

http://www.industrialnoisecontrol.com/comparative-noise-examples.htm

And then also download and listen to this file with a tone at -105 dB (scroll down to mid-page, where it says “the dynamic range of 16 bits”):

https://xiph.org/~xiphmont/demo/neil-young.html

My point is: If you listen to the -105 dB track, then you would realize how big of a difference in volume level there is between the quietest and loudest parts with just 16 bits and how soft -105 dB really is. It’s both too soft to hear at anything else than rock concert levels in your home, and nobody would enjoy listening to these kinds of volume level differences.

Andres, the writer on the Head-Fi page writes convincingly on the topic of high-resolution audio but he’s not completely write about a few things. I disagree that 24-bits doesn’t matter to recording quality and shouldn’t be provided to consumers. CDs with dither top out at about 93 dB and there are plenty of musical transients that eclipse that dynamic range. Do we find commercial pop/rock/classical/jazz recordings with dynamics greater than a CD can handle? No, we don’t. But that doesn’t mean that we should accept limits dictated by an industry interested in sales not fidelity. I agree that the typical listening environment has lots of background noise and that listening at anything greater than about 85 dB SPL is unwise. But once again, why should I as a record label specializing in ultra high-end albums tailor my products to the least common denominator? I started my label to demonstrate that it is possible to record and release recordings that posses more fidelity than what was currently available on analog tape, vinyl LPs, and CDs. I think I’ve shown that. 16-bit is more than sufficient for virtually all music produced and consumed by the masses. For those rare few that have highly capable systems, specially constructed low ambient noise environments, and motivations to experience the ultimate in musical fidelity, native 96 kHz/24-bit PCM music can deliver it. Why compromise when you don’t have to? (BTW It’s a very specialized 16-bit dithered file that can deliver 105 dB of dynamic range. That dynamic range is NOT possible of a commercial music CD!)

The dithering that the writer on Head-fi talks about is in the A/D-converter, not in the DAC, which is what explains why bit-depth is not resolution as so many people think.

In any case, as we talked about on your other post, let’s see if we can actually hear a difference between your hi-res recordings and CD standards. If we can’t, then I find it pointless as a consumer to buy hi-res.

But again, I fully encourage people to record at 24 bits, but as a delivery format it’s superflous – especially if we listen at 85 dB (including background noise), since we won’t be able to hear any sounds below the 96 dB limit of the redbook format anyway.

As I might have said before, Laurence Juber’s “Guitar Noir” is the best recording I have ever heard, so I complement you strongly on your skills in the studio, and it’s perfectly fine for me that you record at 24/96, but because you created such stellar recordings doesn’t mean it’s because of the format, as you also admitted in your other post, where you said you couldn’t hear the difference between the hi-res version and the downsampled version.

As for the -105 dB tone, then I burned it onto a CD and played it on my CD player to see how much I had to turn up my amp to hear it. It was almost at completely full volume, which is what really put it into perspective for me. But as long as this dithering is applied in the studio, you can play it at home it seems. Anyway, turning up your amp to be able to hear that tone at -105 dB really shows how unimportant any musical content at those volume levels are.

I do have a hard time hearing high res qualities in studio “pan pot” recordings with little natural ambience.

However, high res qualities in raw DSD recordings of orchestral music are clearly evident and to my ears better sounding than even the same recording processed at 384khz PCM for production purposes. It is hard to find raw DSD recordings in a world that produces spliced together orchestral recordings in order to synthetically create the perfect take. The conversion back and forth between the DSD and the PCM removes spatial information that is captured in the original DSD recording.

I am open not only to challenges to this comment but also explanations of why I hear the difference so profoundly. I would not think of making this comment if I had not already assured myself that I can pick the raw DSD recording every time.

-Casey

Thanks for posting. As a vowed critic of DSD, I’m not a fan of the technology or results. A rigorous study done in Germany a few years ago concluded that trained listeners and musicians couldn’t tell the difference between a DSD and PCM recording (DSD 64 vs. 96/24). They made a new recording of a chamber music ensemble from the same mics and preamps to both formats. I believe they would sound virtually identical. However as you rightly state, there’s not way to produce audio using 1-bit DSD. There are a few labels that make it work (Channel Classics) but others convert to PCM, use DXD (which is PCM), or stay in the analog domain until the last possible moment.

Casey, do a level-matched (down to 0.1 dB) blind test between the DSD version and the version you converted to PCM, and make sure they’re perfectly aligned, and see if you can tell a difference. If you can, then we can try to figure out why you can hear a difference (perhaps there’s a problem in the conversion). If you fail the blind test, it was probably just placebo.

It sounded like you converted the DSD files to PCM yourself, but in case you downloaded each version, the label might have doctored the PCM to push DSD on their customers (there have been reports like that before), or something else might have gone wrong somewhere.

I’m just a lowly otolaryngologist who happens to agree with you but at age 79 I doubt that I can hear the high frequencies let alone the ultrasonics. But to do a true double blind study, you would need to assemble a statistically significant number of test subjects that had first been tested with audiograms that showed they were capable of hearing at least to 20kHz with some ability to appreciate ultrasonics. Then get them individually to hear a properly recorded and played set of music of various types and record their impressions. Who would fund such an enormous task? Here’s a simpler solution: Get the original recording artists to listen to their own music recorded and played back with and without the ultrasonics and higher dynamic range and see if they can identify the difference.

The ultrasonics are more about technical accuracy than perception IMHO. Despite claims by some authorities to the contrary, there are procedural benefits from using 96 kHz — less stringent filters and less IM distortion. The addition of 24-bit, when maintained through to the delivery of the final master (which is very rare), can make a difference and be perceived. It’s not black and white but does deliver a more true to life experience.

I have been reading your blog for a few years now and have purchased a few of your offerings. I can understand your basic mantra of ‘Garbage in, garbage out’ or ‘Quality in, quality out’ but you also seem to be saying that you are one of the few sources offering ‘Quality in’. It also seems to me that you are saying that the measure of the best ‘Quality in’ is your 5.1 offerings. I have a very good Linn stereo system and will never possess the hardware for a 5.1 system. This has nothing to do with affordability. The offerings i’ve purchased from your website do not sound appreciably different from any of the ‘high res’ offerings I have acquired from various other websites.

I have also read your recent announcement that you will no longer be offering any new music. Are we to conclude, from your musings, that we will not in future, have a source for the best ‘Quality in’?

Hi Jim and thanks. Your assessment is correct. There are very few labels recording and releasing real high-resolution music. But that isn’t really the focus of the major labels and their roster of artists. They want success, sales, and recognition. The production process of a commercial release requires heavy handed mastering — which reduces the fidelity of the music. But fidelity isn’t the target! All of my AIX releases have two 5.1 surround mixes AND a standard 2-channel stereo mix. While I advocate for immersive music listening, it’s not required. Admittedly, most audiophiles are content with stereo.

If you don’t hear an appreciable difference between a real high-resolution track from my catalog and a typical commercial release downloaded from HDtracks, you’re not alone. However, the vast majority of correspondence tilts the other way. The phone call from Bill the other day was an example. In 50 years, he had not heard anything come close to the fidelity of one of my releases. It’s less about the format, sampling rates, and word lengths. The way that I record and orchestra with dozens of close stereo pairs of the placement of 4 mic inches above the strings in a piano result in a more detailed, present sound. Combined with 96 kHz/24-bit PCM encoding, the results can be dramatically different than a typical recording — even another real HD track.

The quest for really exceptional source recordings has been and will continue to be challenging. For those looking for the ultimate in listening pleasure, there will be always be audiophile engineers and producers willing to cater to that niche. But forget about looking to the major labels. They are businesses looking to maximize return on investment.

Hi Jim,

I will never own a high end system for financial reasons but I have put together a decent mid range 5.1 system and I strongly urge you to do so. I understand the arguments around hi vs standard res audio – the differences are subtle without doubt but 2.0 vs multi-channel IF done correctly by producers like Mark then the difference is like night and day and I find it difficult to tolerate people who seem utterly convinced that two speakers are enough to properly release music back into your listening environment.

Mark

I totally agree with your philosophy that whatever sounds are being produced during a recording they should be captured as accurately as possible and ‘CD quality’ constantly shows those top frequencies being cropped off – I don’t like it!

All of the research projects I’ve examined that have attempted to answer the HD vs standard audio question don’t stand up to scrutiny, (it reminds me of the large number of dubious nutritional research projects that I am more familiar with) the subject numbers are often very small, the equipment and actual sound sources themselves are often questionable. I think it’s essential that people in these tests have access to the various qualities of music for a prolonged period of time – possibly Months as my hypothesis is HD is ‘easier’ to listen to regardless of any definite noticeable difference in quality.

>> The well-know Meyer and Moran that equated the quality of CD vs. SACDs and DVD-Audio discs used only standard-resolution sources!

Please. Not according to their manufacturers!

As we wrote eight years ago in a letter response in the AESJ, ‘[the letter-writer; not Waldrep] cites “many posters to the SACD website” in support of his contention that the recordings we used in our tests were of insufficient resolution. (For those interested in the specifics, our list of sources, and further descriptions of our methods, have been available since late 2007 at http://bostonaudiosociety.org/explanation.htm.) None of our test discs were reissues of old or inferior material; all were recorded with modern microphones and electronics. Many claims of the superiority of high-resolution audio do tout its audibly improved performance even with reissues of old analog recordings. Nevertheless, to address this question we added up all the trials where the original sources were very recent recordings touted as being of demonstration quality from their labels (Chesky, Telarc, ECM, Turtle and Kimber Kable). The average correct score for this group was 45.4% (109/240), slightly lower than our overall average. There were no scores above 95% confidence for any listener.’

But come on and seriously: This is all a bunk debate, complete bunk. The reason it is bunk is that for over a decade the burden has been on the Waldreps and Bob Stuarts of the world and all of their fanboys to honestly show not only that hi-rez, much less ultrasuperduper hi-rez, is audibly different but also that it is preferable. (I will let the reader figure out what ‘honestly’ means.) You would think this would be easy. You would think it would be simple. You would think it would be marked and demonstrable to any savvy listener, much less to truly experienced and widebandwidth auditioners. Indeed you would think that these guys would have done the honest comparison themselves, conclusively, and also involving their golden-eared and educated-ear colleagues, in particular younger listeners and women — and published the results in a refereed journal. Surely, surely, given their claims, this should have been long-settled by now in their favor. But guess what?

David, thanks for coming by my blog site. I addressed the issues raised in your comment in my response to Ethan Winer. In short, any and all SACDs cannot be used to evaluate the perceptibility of high-resolution audio because the format itself is incapable of capturing and reproducing ultrasonics. I became aware of this fatal flaw in the SACD coding scheme when Ray Kimber showed me the spectra of one of his recordings. I was shocked to see the bright red haze emerge just above 22 kHz. Where the quietest ultrasonic partials should have been, there was just noise.

I would love to conduct a similar study with music that does actually possess the requisite extended frequency response and real world dynamics. It would advance our knowledge of audio engineering and human hearing but it would be of academic interest only. The commercial record industry is perfectly happy with CDs, MP3s, vinyl LPs and even analog tape. This is unlikely to change. You trusted the manufacturers of the SACDs provided by your membership. Any analysis of the fidelity those albums would confirm that they are not high-res.

I did not see that you really addressed anything particularly other than just throwing around yet again that the results were “completely invalid.” Oh, and that we ‘trusted’. Well, prove it yourself, man, prove it yourself. It is obnoxious to feign civility as you do. You have made a career out of going around claiming our work is invalid and that there is ultrasonic material that is ‘requisite’. (But, oh no, not SACD! What, just your stuff? Or Stuart’s? Please. Some auditioners brought DVDA, as I recall.) In any case the burden is on you and all who make that claim, even as we do not have the haircells to detect it and never have had. I suggest that you look up and understand what special pleading is, also tautology. Hi-rez is only what you define it as. Yours is the very definition of special pleading.

Go do your own honest study. No pleading costliness. (We didn’t.) I dare you. It’s been >11 years. Make your name in science. Show ultrasonics. Put up or just stfu.

Wow! You consider having a reasoned discussion regarding your study and pointing out what I consider to be serious flaws is “feigning civility” and you end with STFU? Excuse me for challenging the work that you did and published. I am not alone in believing that your work was flawed. My career is not based on pointing out your work was invalid (although as I shown it was). It would seem that the responsibility is on you and others to use content that qualifies as high-resolution. Your defense is that the manufacturers said their releases were high-resolution, so they must be. And you believed them rather than verify that the music possessed fidelity beyond standard Redbook CDs. I have advocated for “real HD-Audio” for over 15 years. The materials you used did not meet my definition of high-resolution and therefore invalidated your study IMHO. Your refusal to acknowledge any errors in your work and to attack those of us who have pointed out the shortcomings speaks volumes. Any continued rude posts will not be tolerated.

Sigh. We used what was widely bruited to be as good content as there was at the time. Is part of this that you are miffed we did not use your content?

There is a difference between flawed and completely invalid, your term.

Who refuses to acknowledge errors in the work? It cannot be that you did not read our letter in response, can it?

So: you should own your offensiveness, I suggest, rather than taking umbrage at sharp responses to it. Your challenge is old. I have posted here in the past, to the same end. Hence my shortness.

Speaking of which, the last line posed a choice for you, not an order. I ask that you and your adherents put up honest evidence for your assertions, humble or not, and have been asking this for over a decade. Stuart already failed in this, epically (wack filter choices).

Why do you think no one has come up with honest evidence? Please go and demonstrate the “audibility of an RBCD-standard A/D/A loop inserted into high-resolution audio playback”, with any hi-rez material of your choosing. Just do it, k?

And then we can test for preference.

You’re right. The commercially available SACDs used in your study were typical offerings in “hi-res”. There were very few new recordings available. That’s exactly the reason I started my own label — the stuff being put out as “hi-res music” was pulled from the existing standard-resolution catalogs and put out in the new format. I wasn’t “miffed” you and the BAS weren’t aware of my records. In fact, I was encouraged when I examined the list of recordings that were used and didn’t see any of my albums.

I have maintained that your study was invalid because none — not a single one — of the albums met my definition of high-resolution. Others may have a different definition. The CEA, labels, DEG, and NARAS accept any master from any period as long as it has been transferred to a high-resolution bit bucket. I hope you would agree that a 78 rpm lacquer disc from the 40s at 192 kHz/24-bits has no chance of being considered high-res. I have been steadfast in my insistence that high-resolution recording must be made using high-resolution capable machines AND exhibit fidelity in keeping with the potential of those specifications. I recognize that the commercial music industry is providing less than that. They don’t have a choice because their catalogs rely largely on standard-res masters or releases that have been processed to remove any of the benefits of high-res. We actually agree that high-resolution is not perceptible — at least as it’s being offered by the major labels and many audiophile suppliers as well.

However, there are recordings that do take advantage of the full potential offered by high-resolution specifications. AIX Records is not alone in this regard. I strive to support my positions with careful analysis, charts, and background. And I acknowledge that at timers I can come across as harsh or condescending — for that I apologize. It is not my intent to criticize you personally. I believe you did the best that you could at the time with the content you were provided. Pointing out the flaws in your study simply points to another day when another party will conduct a better study. For the longest time, I wanted to conduct the definitive study. As I’ve seen the progress of “hi-res music” and been part of its marketing, I learned that the future of audio won’t include real high-resolution recordings. There is no interest in elevating fidelity on the part of the labels, artists, producers, and audio engineers.

If you have followed my recent posts on the topic of high-resolution, you’ll find that I agree with you and Ethan on the need for hi-res in commercial recordings. Compact discs offer enough fidelity. But it’s also true that moving to high-resolution (96 kHz/24-bit PCM) is beneficial during the recording process, it’s cost effective and easy to do, and provides the complete range of real world dynamics. Why not use 96 kHz/24-bits? There are a number of technical (if not perceptible) advantages.

Not so long ago I also believed that whatever source you take and transfer it to hi-res then it will sound better. And this is how hi-res is marketed to the unaware customer. I believed all the stuff about the extra “magic” and so on. Then I investigated and found people like you, Ethan Winer, Archimago, saw the Monty Video and now I know better.

About the Meyer & Moran study:

It has debunked the myth that old recordings will sound better in hi-res. Again: This is how hi-res is marketed to the public and just because the study doesn’t fulfill YOUR demands for hi-res doesn’t make it invalid. I see this study as step 1 in an evaluation process: Old recordings tranfered to hi-res don’t sound better. Check!

Next step would be taking real hi-res recordings like yours which fulfill your demands for hi-res and see if a downsampled version still sounds the same or not. For me personally and I guess for many many others this study was very helpful and an eye-opener when it comes to transfered older (analog) recordings. And I say it for the third time now: This is how hi-res is marketed. Take any source, transfer it to hi-res and it will sound better. I believed it.

Alexander, thanks for the comments. You’re right about the M&M study and I actually wrote a blog post a long time ago reinforcing your point. The test was invalid with regards to the hypothesis it posed. But if they had sought to answer the question of whether a standard-definition master recast in a high-resolution bit bucket is perceptible, then it hit the nail on the head. Good point.

Well, lest a new reader be misled, none of those were *old* recordings in any usual sense of the word, like taking some Stones or Eagles or NYPhil tape from the 1970s or before and putting it on CD. Read my June 10 quote above of our AESJ letter response, and/or see the list at the link.

you are a worthy purist and idealist, Mark

there is no reason not to record at higher rez , as we and many others have written over and over; we were testing for audible transparency of delivery medium and nothing other.

you should do the honest test of your theory regardless of the marketplace and the future!

David, it seems we have some agreement. That’s progress on am always contentious issue. Yes, I would love to manage a rigorous test of perceptibility or whether human brains react differently to high-resolution source materials. I’m going to write a post today to address some of these additional thoughts and continue with the exploration that Ethan posed to his readers.