Music Composition 101

I started seriously studying music when I moved from Michigan to California back in the 70s. I enrolled at Santa Monica College, took private piano lessons (mostly classical repertoire) and continued playing acoustic and electric guitar. I was extremely fortunate to have really great teachers at every turn…teachers like Gaylord Mowrey. I met him at SMC where he was the staff accompanist. He could read anything from the page and play it…just like you and I might read a passage of a book out loud. This was somebody that I wanted to get to know. It turns out that he changed my life!

Every Saturday morning, I would go to his place (a guest house in Venice) and spend two or three hours listening to music, playing music, listening to him play music…and tasting the occasional glass (bottle?) of wine. As is the case with a large number of beginning piano students, I learned a couple of the Bach two part inventions. This set of pieces are simple two part counterpoint where the top line (the right hand) plays a melodic line and then trades off the spotlight with a melody of equal importance with the bottom line. The pieces are basically conversational in nature…each participant takes the foreground for a few measures and then sits back while the other party moves into the spotlight. This contrapuntal style of music was all the rage in the Baroque period, which lasted from roughly 1600 to 1750 (not coincidentally the year of J.S. Bach’s death).

Bach’s music requires tremendous technique and mental focus on the part of the performer and the listener. I had always thought that classical music was simply nice sounding melodies and harmonies. After all, my background was in acoustic folk music and improvisational jazz. What I didn’t realize was that “classical” music is composed. It’s not merely pretty sounds played by an ensemble or soloist. There is an intellectual side to the assembling of notes, chords, structures and forms in music. Who knew?

The first two-part invention of Bach is a perfect example of this. When I used to teach music theory, I would demonstrate the piece and all of the relationships between the melodic lines. In the words of the English 19th Century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (28 July 1844 – 8 June 1889), the invention was a dramatic example of how, “all’s to one thing wrought” (which was the opening quote in my musical form textbook).

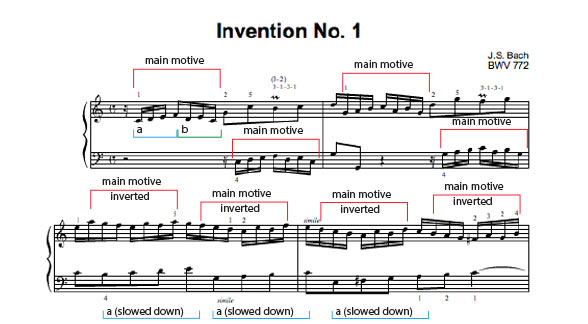

The first invention starts with a simple ascending four-note motive followed by a descending pattern of skipping thirds (see Figure below). Then the same line is given to the left hand before he lays out some sequences of notes that propel the piece into the dominant key (a perfect fifth higher than the original line). But if you look carefully at the intervening sequences, it’s all the same stuff that was in the opening line. Sometimes it’s turned upside down and other times the speed is changed. In fact, there’s not a single moment in the entire work that isn’t directly related back to that opening motive. Bach ties everything together in the same way that Beethoven famous fifth symphony used the four note opening idea (da-da-da-dum) throughout the rest of the entire symphony!

Figure 1 – The opening of Bach’s first invention with analysis showing relationships to the original motive.

This is music that is carefully constructed or composed using techniques that have continued to evolve as each new generation of composers passes. The entire history of music is a careful balance between adherence to the establish practices of the day and the incessant mission creep of originality and imagination. Just imagine what the reaction would be if we could time travel back to Bach’s time and let him experience a string quartet from Elliot Carter. His mind would be blown! But the truth is there is a common thread between their compositional processes.

Bach is my favorite composer. There are other giants out there…but for me there is nothing like the Art of Fugue or the Musical Offering. My slant to the intellectual side of musical expression started when I began to know Bach and his music. And the fact that we share the same birthday (a couple of centuries apart!) capped it.

If you don’t know his music, take an afternoon and do some research. Listen to a variety of his work and you may come away with an appreciation of counterpoint that had eluded you.